But its history – especially the bits that have been forgotten – tells us a lot about how we have framed our colonial past, particularly in relation to architecture.

Typically, New Zealand’s earliest non-Māori buildings were depicted as having a direct lineage with imperial Britain. As one of our earliest architectural histories (written by Christchurch architect Paul Pascoe and published for the 1940 centennial) put it: “Our architecture derived from England.”

But as my recent research has found, this isn’t the whole story. In fact, it obscures another important strand of New Zealand’s early development, which reveals how the evolving colony wanted to see itself.

‘Little more than shacks’

At the time the first jail was built, Okiato was the colony’s administrative capital, close to Kororāreka which Governor William Hobson renamed Russell.

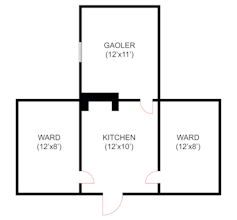

The building consisted of two windowless cells, with a central kitchen and a back room for the jailer. It was located in a yard surrounded by a three-metre-high log wall, and was built by men from the 80th Regiment at a cost of £420.

Christine McCarthy

Architectural historian John Stacpoole (1919–2018) described it as one of a series of buildings that were “little more than shacks”, and on the surface it doesn’t sound terribly special. There was no Victorian grandeur that might be typical of a civic building, and it wasn’t built of brick or stone as English prisons were at the time.

And there was a reason for this. The jail was designed in the Colonial Architect’s office in New South Wales. As such, it was a direct import from Australia’s convict system.

Most New Zealanders probably think of their country at that time as a British colony. But before it became its own distinct colony, Britain extended the boundaries of the colony of New South Wales to include New Zealand.

This arrangement lasted almost a year, but is often forgotten or overlooked. Partly this is because considerable effort was put into distancing New Zealand from the convict “taint” of Australia’s penal colonies.

Australian designs

There is further confusion over the jail’s designer. The architect usually credited is William Mason (1810–97), who was employed by the New South Wales Colonial Architect’s office before arriving in New Zealand.

Mason is better known for buildings such as Government House in Auckland (1856), All Saints Church in North Dunedin (1865) and the Stock Exchange Building in Dunedin (1868, demolished in 1969).

But the Okiato jail design wasn’t one of Mason’s. It was actually a standard plan designed by Ambrose Hallen, also from the Colonial Architect’s office.

Hallen’s time as colonial architect from 1832 to 1835 coincided with a government policy of territorial sprawl in New South Wales, which included building more judicial and penal infrastructure.

The policy required the design of what Australian prison historian James Kerr has called the “basic plan”. This was adapted across state as a watch house, a lockup and a jail for more than half a century.

An example is the Goulburn Plains design, which incorporated a timber weatherboard courthouse straddling the stockade surrounding its log jail. Another version added a room for the jailer behind the kitchen’s fireplace. It was this design Mason had built at Okiato.

How and when history is told

The forgotten influence of the New South Wales Colonial Architect’s office on New Zealand’s earliest prison architecture surely relates in part to the building’s apparently rudimentary nature.

Simple log buildings fit with a pioneering, frontier myth of transience and impermanent architecture. This sits at odds with the sophisticated skills already evident in 1840s Aotearoa, including Māori expertise and the craftsmanship of British and US ship carpenters.

But it may also be to do with how we tell the histories of our colonial architecture. Consistent with Paul Pascoe’s assertion that local architecture “derived from England”, our first jail buildings have perhaps been measured against English prison architecture and found inadequate.

But the jail at Okiato was not a makeshift one-off – a deliberately designed structure that links the young colonies of New South Wales and New Zealand in ways that help us understand our early European history.

Alas, it no longer exists. After ten months, Hobson left Okiato and established a new capital at Tāmaki Makaurau-Auckland. References to the jail suggest it operated until about 1844.

The Okiato jail might not have loomed large in New Zealand’s architectural histories, but the story of its origin is nonetheless a useful one. It’s a healthy reminder that history has a complex relationship with “the truth”, so we need to constantly reexamine it.

This article written by Christine McCarthy, Senior Lecturer in Interior Architecture, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Discover more from Future of Society

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.